The Sound of Silencing

A string of recent incidents suggests that freedom of expression in Japan is vulnerable.

By Gavin Blair

In February, the director of the “Yasukuni” documentary and staff at his production company received death threats, and in March a number of cinemas pulled the film after pressure from politicians and nationalist groups. April saw a freelance journalist ordered to pay compensation for libel over an article he didn’t write but was quoted in. In May, 38 demonstrating students were arrested for trespass on their campus at Tokyo’s prestigious Hosei University and detained without charge for three weeks. In June, the Supreme Court overturned the findings of two lower courts that NHK had buckled to political pressure in altering the contents of a program about WWII sex slaves. Are these disparate incidents evidence of a lack of protection for the right to freedom of expression guaranteed in Japan’s Constitution?

Are these disparate incidents evidence of a lack of protection for the right to freedom of expression guaranteed in Japan’s Constitution?

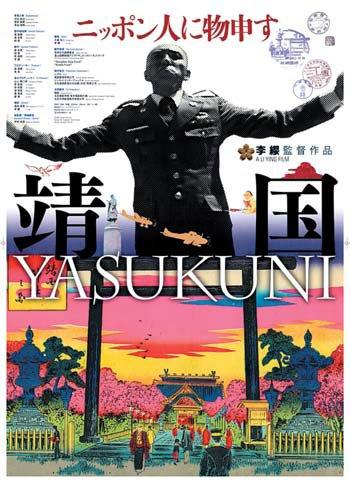

Yasukuni

Before it was even released in Japan, ‘Yasukuni’— a documentary focusing on the shrine dedicated to Japan’s war dead—was attracting nearly as much controversy as the place itself. When it emerged that a ¥7.5 million grant had been given by the Agency for Cultural Affairs to help make the documentary, LDP politicians questioned why the film, which was being called anti-Japanese, had received public funding.

Yasukuni, the documentary, was the center of a freedom of speech controversy

Yasukuni, the documentary, was the center of a freedom of speech controversy

“We were approached by the Agency for Cultural Affairs to arrange a screening of the film for politicians before it was released,” reports Aki Nagamuro from distributor Argo Pictures, on a move seen by some as backdoor political censorship.

Naoji Kariya, the last surviving Yasukuni swordsmith, features prominently in the film and had given his support after watching a preview. However, after being contacted by House of Representatives’ LDP member Tomomi Inada, he subsequently made statements to the media about wanting his scenes cut. Inada denies influencing him.

Although a number of cinemas cancelled screenings of the documentary in the wake of the controversy an ‘uncut’ version of ‘Yasukuni’ was eventually shown in a limited nationwide release. “In the end this was something of a victory in that the film did get seen despite fairly blatant attempts at censorship by politicians,” says Professor Lawrence Repeta of Omiya Law School.

NHK: Freedom to censor?

Another case with roots in the still-thorny issue of Japan’s wartime conduct surrounds a broadcast of a mock-trial dealing with wartime sex-slavery, aired by NHK in January 2001. The citizens’ tribunal featured in the program was organized by seven NGOs including the Violence Against Women in War-Network Japan (VAWW-NET Japan) and found the wartime government and Emperor Hirohito guilty of allowing the institutionalized sexual slavery of tens of thousands of women.

Immediately prior to broadcast, four minutes were cut from the program including the ‘verdict’ and interviews with an army veteran and a former sex slave.

VAWW-NET Japan sued NHK, claiming it had caved to pressure from senior LDP figures, including Shinzo Abe. In 2007, the Tokyo High Court confirmed the 2004 findings of the Tokyo District Court that then Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Abe (later to be Prime Minister) met with executives from the public broadcaster the day before the program was aired and pressured them to edit the contents.

Despite the whistle-blowing testimony of a senior program producer that external pressure had led to the changes being made, the politicians and NHK denied any censorship occurred. The Supreme Court decreed NHK was free to edit the program as it wished and had no duty to justify its decisions.

Libel and intimidation

On April 22, Tokyo District Court found freelance journalist Hiromichi Ugaya responsible for libel over comments that were attributed to him in a Saizo magazine article about the relationship between music-chart compiler Oricon, and the all-powerful ‘talent’ agency, Johnny’s Entertainment.

Ugaya claims he was misquoted in the article, written by a Saizo editor, and had asked the magazine to remove his ‘quotes.’ During the court case, Ugaya says he found himself in the somewhat surreal situation of being asked by the judges to justify allegations he never made.

Another unusual aspect of the case was Oricon’s decision to sue only the interviewee but not the publisher, magazine or editor. Atsushi Naito, a Tokyo-based entertainment industry lawyer, says this would usually happen only when, “the writer or publisher was simply relaying information that had been provided or quoting somebody in an article, then they are relieved from responsibility for libel.” In this case however, Ugaya’s (mis)quotes were used to back up the writer’s argument about the relationship between Johnny’s and Oricon.

Although the ¥1 million in damages Ugaya was ordered to pay is a fraction of the ¥50 million Oricon had sought, he already faces a legal bill of nearly double that amount and says the case has affected his attitude to reporting, “After I got sued I wrote a short article about why the Walkman lost to the iPod. It wasn’t a controversial piece, but what was on my mind was—what if I get sued by Sony? In that sense Oricon did a very good job intimidating me.”

Ugaya is currently appealing but likely faces an uphill struggle. “The courts in Japan have not established the kind of strong protection that the media in, say the US, enjoys when writing about public figures or corporations involved in matters of public interest,” notes Professor Repeta.

Muffling student rumblings

On May 28 and 29, a total of 38 students who were protesting against the G8 Summit were arrested on their campus at Tokyo’s Hosei University. The campus dispute dates back to 2006 when outside security guards were brought in to prevent some student groups from putting up posters and handing out fliers. A number of the groups were then proscribed, 60 security cameras were installed, along with guarded security gates allowing only single-file entrance to the campus. The day before the campus demo on May 29, three students were arrested on charges of ‘personal injury’ and two for ‘obstruction.’ The students claim these are trumped-up charges and the five were arrested because they were leaders of the protest.

At a June 19 press conference at the Foreign Correspondents Club, representatives of the students showed a video of a small, if somewhat noisy, protest on the Ichigaya campus being broken up by scores of Public Security Police. A total of 33 students were arrested for trespass and held along with the other five at 35 different police stations across Tokyo. Later on, 19 of the students were released without charge following three weeks’ detention, and 13 indicted for trespass.

Hosei University, the scene of student protests

Hosei University, the scene of student protests

Fumito Morikawa, a lawyer representing the students says, “The students have a right to demonstrate on campus and this is an issue of freedom of expression. A university is a public open space. Arresting students for trespass on their own campus and banning political activism should be viewed very seriously.” Hosei University, which is refusing to speak to the press, is a private institution and had banned some of the students involved from the campus. This pushes the trespass issue into a grey area.

“Even though the lower courts sometimes rule against the Public Security Police and other government agencies in cases like this, the appellate courts almost always overrule them,” says Professor Repeta.

“In cases of freedom of expression, the responsibility ultimately lies with the Supreme Court,” he explains, “It has only ruled government action unconstitutional eight times in the sixty years the constitution has been in place, and it has never done so on an issue of free speech. The result is that the prosecutors and the police effectively get to decide what is legal in cases like this.”

The robust protection for freedom of expression enshrined in Article 21 of the constitution means little if the Supreme Court fails to support those ideals in its decisions. With judges to the top court politicallyappointed, and the chances of the LDP losing power looking higher than they have for decades, there is some hope for change. However, any new appointments to the top court would take time to make their mark and there are no guarantees that their attitude to freedom of expression would differ greatly from that of the incumbent judges.JI