Tokyo Queues For You

Why you have to wait two hours for a doughnut in Japan.

By Florian Kohlbacher and Uwe Holtschneider

Queuing is nothing special in Japan. Every day, television programs show long lines of people queuing for up to one hour, even in front of regular noodle shops, only to finish their food within less than ten minutes. Now, the Tokyo branches of the American doughnut chain Krispy Kreme are taking this phenomenon to a new level.

Since its opening in December 2006, a persistent waiting line has formed in front of the first branch at Shinjuku Southern Terrace. For the two-minute bliss of a Krispy Kreme doughnut customers are willing to wait patiently for at least one hour and at peak times, two or even three hours long. Krispy Kreme has now expanded to Yurakucho in the east of Tokyo and Tachikawa in the far west, as well as to the city of Kawaguchi (Saitama) and Funabashi (Chiba) and most recently to Shibuya. What is Krispy Kreme doughnuts’ formula for success?

Krispy Kreme

Krispy Kreme

The first Krispy Kreme shop was founded in 1937 in North Carolina, but nationwide expansion in the US did not happen until the 1990s. As a result of expansion, the stock price, which performed excellently after the IPO in 2000, experienced a sharp decline after only a short period of time. Sales of the sugar-glazed calorie bomb (with at least 210 calories in its classic, ‘original glazed’ variation and up to 390 calories in a ‘Krispy Kreme Devil’s Food’) have declined, hit by the trend towards healthy eating. Some observers see few alternatives for Krispy Kreme in the long run because of its one-sided product line. Many believe the chain will not last in competition with the coffee and fast-food giants Starbucks and McDonald’s that have greater flexibility in responding to such market moods.

Since 2001, Krispy Kreme has been following a strategy of internationalization that, to some observers, looks like an emergency road out of the increasingly hard doughnut business in North America. After conquering the markets of other Asian locations such as South Korea and Hong Kong, Krispy Kreme turned to Japan and entered via a joint venture with the retail experts from Lotte Co and Revamp Corp. The run on the Shinjuku branch proves that the cooperation with local partners paid off.

Doughnuts in Japan

Doughnuts are nothing new in Japan. Starting in the late 1970s, the two big chains Mister Donut and Dunkin’ Donuts entered the Japanese market almost at the same time. Nowadays, doughnuts can be purchased in many supermarkets and restaurants. Unlike food-service chains such as McDonald’s or Starbucks the doughnut business did not face competition from local imitators. In 1998, Dunkin’ Donuts left the market so that only Mister Donut remained in Japan with more than 1300 shops. The different performance is said to relate to differences in management strategies, not in quality. So far, it seems that the newcomer Krispy Kreme has a winning strategy.

But why is it that for more than one and a half years now, people queue outside of Krispy Kreme every day? Is it really the unique taste thanks to the ‘secret recipe’? Even though customers do attest Krispy Kreme doughnuts’ excellent taste, that alone is not likely to make people queue for an hour facing rain, wind and darkness for a product that is quickly consumed and whose substitutes can be found almost anywhere.

The waiting line phenomenon

The easiest answer is: Japanese people love queuing. Just like an excessively high price can evoke an image of equally high quality, long waiting lines act as an indicator for popularity, reduce availability and increase the subjective value of a good. Thus, for many customers, waiting lines are more attractive than daunting. Standing in line also increases and extends anticipation until— yatto! (finally!)—patience is rewarded with the desired product. In other words, Krispy Kreme doughnuts compensate the labor of waiting, basically a modern interpretation of hedonistic calculation. When taken to an extreme level, the product one is actually queuing for ceases to be of any importance at all. In an article published in The Japan Times in summer 2007, a Japanese woman confessed that she enjoyed queuing outside shops and restaurants and that she usually joins the line before asking the person in front of her what kind of product is sold.

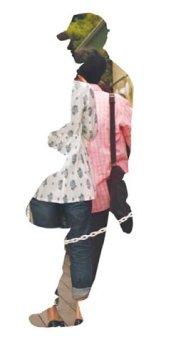

Were they paid to be there? -- Photography by Sarah Noorbakhsh

Were they paid to be there? -- Photography by Sarah Noorbakhsh

Waiting lines have become a marketing tool. ‘Benriya’-service companies, which offer all kinds of unusual services, provide rentable ‘queuers’ who form or extend lines. Customers who are not willing or unable to wait can also rent a queuer who will stand in line and purchase the desired product for them. Obviously, this service is not free of charge, plus customers not queuing themselves will miss out on the freshly baked doughnut handed out for free to everyone waiting in the line. Extremely hungry clients can also opt for the much shorter ‘Express line’ and buy a dozen of already packed standard doughnuts.

Considering the appeal of the Krispy Kreme waiting line, it would not be surprising to find professional queuers in the line to increase the image of a hard-to-get product and make customers want to join the line. Of course, this is pure speculation but to keep the line in front of Krispy Kreme in shape, the wage of a few Benriya-employees would be a minor investment compared to what would happen if the queue suddenly disappeared.

The Krispy Kreme marketing recipe for Japan: The 4Ps

The classic marketing concept of the 4Ps explains factors for the huge success of Krispy Kreme in Japan:

Product: Although doughnuts are a very standardized product, Krispy Kreme has succeeded in creating brand-specific characteristics and a strong product name by referring to tradition and a ‘secret recipe.’ Thanks to the ample variety of doughnuts, everybody can pick out his or her favourite.

In a PR spiral, the waiting lines of people outside the store in Shinjuku also keeps hitting the headlines

Place: Shinjuku station is one of the largest stations in Tokyo and is widely used by commuters from the western suburbs. The immediate neighbourhood includes the luxury department store Takashimaya, Starbucks and a variety of other premium stores.

As Simon F Cooper, President of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, put it in the April 2007 issue of the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Japan’s magazine Japanmarkt: “Here in Japan luxury and big names must be surrounded by luxury and other big names.” The environment of the Krispy Kreme shops thus enforces the image of a premium product. Besides, the stores are strategically located in areas popular among younger people, their main clientele.

Price: Priced at ¥160, Krispy Kreme’s ‘original glazed’ doughnut is more expensive than the basic doughnut of its competitor Mister Donut (¥126). With this premium positioning, the chain literally follows a ‘skimming-the-cream-strategy.’

Promotion: Krispy Kreme has presented itself as something special from the very beginning. A television crew documented the opening of the new shop and praised not only the special process of manufacturing and the ‘secret recipe,’ but also the ‘unique’ taste of the inimitably soft doughnuts. The show also broadcast Krispy Kreme staff handing out 500 free packs of 12 doughnuts each to passersby—standard practice whenever a new Krispy Kreme branch opens. Besides this, the doughnuts have appeared on several TV-shows and, in a PR spiral, the waiting lines of people outside the store in Shinjuku also keeps hitting the headlines. All the rest is kuchikomi: word-of-mouth recommendation.

Queuing as a marketing tool

Does the Krispy Kreme model apply to other products and services as well? Success is not always guaranteed because the attractiveness of waiting in line can easily backfire if the desired product does not meet expectations. Krispy Kreme does offer a special taste that, thanks to skillful branding, seems to justify a premium price. Quality management is characterized by modern IT infrastructure and CRM (Customer Relationship Management). However, the final question is whether its success in Japan will last. Considering Japanese customers’ constant demand for innovation, the present hype might vanish over time. In the end, only the opening of yet more branches will show how ongoing the fascination of a queue really is. We’ll wait and see...JI

An earlier version of this article was published in German in the August 2007 issue of JAPANMARKT, the leading business magazine on Japan in German language published monthly by the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Japan (GCCIJ) in cooperation with the Swiss Business Hub Japan

The Authors:

Dr Florian Kohlbacher is a research fellow at the German Institute for Japanese Studies in Tokyo. He teaches business and management at several universities in Tokyo and is the author of “International Marketing in the Network Economy: A Knowledge-based Approach”, Palgrave Macmillan 2007 and the co-editor of “The Silver Market Phenomenon: Business Opportunities in an Era of Demographic Change,” to be published by Springer in autumn this year.

E-mail: kohlbacher@dijtokyo.org

Uwe Holtschneider is a research associate at the Chair of East Asian Economics, Japan and Korea at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany, where he is writing his dissertation on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) of Japanese companies. He is currently a member of a research project funded by the Austrian Chamber of Commerce Vienna. The study comparing CSR in Austria, Germany and Japan will be published in summer this year.

E-mail: uwe.holtschneider@uni-due.de

The authors would like to thank Julia Lange for her help in translating the article.