Japanese Hospital Guide

Tips for choosing physicians and hospitals.

by By Emily Kubo

John wakes up one morning with an ache in his abdomen. It was almost like a stomachache, except it wasn't concentrated in his stomach area. It was a throbbing pain in his abdomen. He rushes to a clinic near Tokyo Tower.

"It might be your appendix," says the doctor. "But we can't be sure. Why don't you go home for now and see how you feel tomorrow. "The next day, John wakes up with a sharp pain in his lower right abdomen. Back at the clinic, the doctor on call took an MRI. "You need to go into surgery right away," he said. John was referred to a foreigner-friendly hospital equipped for surgery.

On the way to the hospital, John calls his doctor in Hawaii. John was skeptical about the Japanese healthcare system.

"Oh, it's not a big deal," his doctor back home assures him. "Nowadays, everyone performs the removal using a laparoscope, so the incisions are small and the recovery won't be so bad."

At the hospital John says "Laparoscope!" between attacks of pain. "Are you performing this by laparoscope?"

"Ahhhh, laparoscope...eh-to...not popular in Japan," the doctor says with an expression that one often sees when new-to-Japan foreigners ask a waiter if they can switch something on the fixed menu. "Only open surgery here." John is quickly ushered into the surgery room.

In comes the nurse, visibly nervous about communicating in English.

"Would you like a big room?" she asks gingerly. "Yes, please!" Knowing space is precious in Japan, he of course wanted a BIG room. A trader at a major foreign bank, he figured he could afford this small indulgence under the circumstances.

John wakes up from surgery indeed in a big room, shared with six other patients, all of them old men who snored loudly. It is then he realized that the well-intentioned nurse had literally translated Japanese oobeya as big room, although the word refers to a room with many hospital beds partitioned by curtains. Heavily sedated, John drifts back to sleep to the rhythmic snoring of his roommates.

The Japanese hospital system at a glance

While deemed as the best in the world by the likes of the World Health Organization, the Japanese medical system itself is said to be wrought with many ailments. In choosing the appropriate health provider, you must first understand how it works. No one understands the system better than John Wocher, the executive vice president of Kameda Hospital, Chiba, who has over 40 years in the medical industry: "The difference between the Japanese hospital and its Western counterparts lies primarily in its fundamental structure: hospital accreditation, physician continuing education, and also cultural differences."

Hospital accreditation is a system in which an independent third party evaluates standards of care according to a set of criteria. Although the Japan Council for Quality Health Care (JCQHC) was founded in 1995 to implement third party accreditation of hospitals, participation in the accreditation process is voluntary. According to JCQHC's official website, 1,997 out of 9,077 hospitals (22%) have undergone the process to meet minimum standards as of March 2006.

Japan's medical system also differs in physician licensing. In Japan physicians are licensed for life. Although Japan is not the only country to do so, physician regulations seem unusually lax for a developed country: "You have to go and get a re-check on your driver's license," points out Mark Colby, CEO and Chairman of Colby International, which localizes clinical laboratory accreditation and physician education in Japan. "But once you become a doctor here you are licensed forever." This is in contrast to the US, where, depending on the state, physicians must go through mandatory continuing medical education and be periodically re-certified. What this means in theory is that a Japanese physician can stop practicing for 20 years, decide to open a clinic, and hang a shingles - without ever having to open another book.

Also in the U.S., if the physician wishes to be a specialist, not only will he/she need to undergo specialized intensive training, the individual also must be re-certified periodically based on continuing education and further examinations. This is not the case in Japan. "For all practical purposes, there are no absolute specialty requirements outside of the university systems," Colby says. "And theoretically, if you are a Japanese doctor and you want to be a brain surgeon, all you have to do is to print yourself a business card. There is nothing illegal with it. And all you need is a willing patient to chisel." Although professional societies that recognize specialists do exist in Japan, and hospitals restrict certain procedures to recognized specialists, physicians here have wider latitude, particularly in smaller hospitals and in private practice.

What this all means, then, is that a physician can basically call him/herself a specialist without a lot of actual experience in their purported area of expertise. Unsurprisingly, one may very well find that the standards of medical care can vary greatly from one physician to another. Finding a competent, experienced physician, then, could be the luck of a draw. Especially beware of smaller hospitals: they may conduct only a few particular types of procedures in a year. Thus, potentially the physician performing a procedure may have limited experience in that area.

This point is emphasized by Guy Harris, an osteopathic physician and the CEO of a Tokyo-based medical documentation company. "The problem is that patients don't really have any way of knowing the level of care and expertise. Perhaps more than elsewhere, it is a bit of a gamble here."

So given the lack of transparency, why would a non-Japanese resident choose healthcare in Japan? For one thing, the Japanese people do have the reputation of being one of the healthiest populations - living and working well into old age. (The Japanese government likes to attribute this to the merits of its universal healthcare regime, although many critics would point out that these statistics are due more to the Japanese diet and lifestyle.)

But perhaps the greatest divide between Western and Japanese medical care lies not in structural differences as much as cultural attitudes. Japanese physicians are not used to being questioned about their clinical decisions by patients, nor are they used to patients suggesting changes in treatment. "Westerners are very demanding. They have to know everything about the care that they are getting. For many Japanese physicians, it becomes very confrontational," Wocher explains. "Many foreigners are also ethnocentric - they think Japan is a developing country when it comes to medical care - fewer private rooms, no amenities like the West. But I think it's a mistake to think that because of those differences, the level of care is not as high."

Colby also notes that there are indeed many positive elements in Japanese healthcare. For one, the plentiful smaller clinics allow you to develop personal relationships with your physician: "Many people have been going to the same doctor for many years to get their meds. So once a month or so, he sees you, he touches your hand, takes your blood pressure, looks you in the eye. So if there is ever a problem that is probably more severe than your normal health issues, you can actually talk to him. Versus if you go to a large hospital - they don't know you, you don't know them."

Primary and Preventative Care

Because of the personal relationship that one might establish with a single physician, Colby favors smaller clinics for primary care, using them as a portal to large hospitals in case of serious conditions. They are not hard to find, numbering more than 90,000. He especially recommends clinics for most people under forty and with minimum healthcare issues that require getting medicine on an ongoing basis.

Many primary care physicians have practiced or trained overseas. Such physicians can speak some English and also understand non-Japanese patients expectations. And because it is difficult for Japanese physicians to receive visas for fellowship programs, those that do will have had to have met the rigorous requirements. A fellowship is perhaps an indication of competence and motivation.

Many doctors, in fact, do advertise in English. Doctors who speak your language can also be found by calling your embassy. Then there is Tokyo English Lifeline (http://www-.telljp.com/) and Japan Helpline (http://jhelp.com/en/jhlp.html). Both offer anonymous, free counseling in English and are good first steps in looking for English-speaking health providers in your area.

A good way to start looking around for physicians before you get sick is to start with the ningen-dokku (human dock), or preventative healthcare checks - a full-blown examination in which physicians check everything. "I do one of those every two years," Colby says. "I started doing the overnight one when I hit 40. If you do that with your primary care physicians, you don't get three minutes of their face time - [with ningen-dokku] you get an hour and a half to two hours, where you are actually communicating and they are checking everything about you."

Ningen-dokku is available to everyone - virtually every general practitioner has his/her own ningendokku system. At large hospitals, separate corporations run them, making them for-profit (as opposed to many of the non-profit government affiliated hospitals). Although ningendokku are not covered by National Health Insurance (NHI), 11 million a year are performed. Colby's research shows that out of those 11 million, about 8 million are paid for by companies, with the rest paid for by individuals - evidence of the ningen dokku's popularity with Japanese citizens.

Beyond Primary Care

But what happens when your needs go beyond preventative and primary care? What happens when you get really sick, or require surgery?

You should get to know a desirable hospital before you have chest pains in the middle of the night.

The experts agree that choosing a hospital will largely depend on patient needs. Hospitals that are really good at cardiovascular surgery, for example, may not excel at the sort of care that you need. For any type of surgery, Wocher suggests that the consumer ask questions about the length of stay, the physician's experience (number of cases), use of antibiotics, and potential complications - all part of the informed consent process. In other words, patients should not hesitate to bring their concerns to the physician's attention. In short, you should get to know a desirable hospital before "you have chest pains in the middle of the night."

Harris agrees that foreigners should do their homework: "What I would do is to look through the medical literature and find a physician who has published papers in the particular area of care needed and find out more about that person. Probably ring them up and see what they have to say." Harris continues: "Though it will likely require persistence and resourcefulness, it's something that people should do and don't do." Keep in mind, however, that sometimes it may be difficult to get the necessary information over the phone. Therefore, making an actual appointment to talk to them in person may be an even better way to get answers as well as start the patient/physician relationship on the right foot.

But before phoning up and visiting a physician, Harris recommends doing research on your specific condition in Pubmed, a medical literature website operated by the US National Library of Medicine. A search of this website will give you the names of Japan-based physicians who have published studies on your condition. The presumption is that physicians who have published research studies are experts in the condition that ails you. Pubmed also lists the institutions that the physicians work at, and sometimes even their email addresses. The next step is to contact a hospital and ask to speak to or make an appointment to see the physician.

The importance of research can't be exaggerated. In Japan a patient gets an average of three to five minutes of face time with a hospital physician. So it behooves the patient to improve on this time by knowing what to ask beforehand.

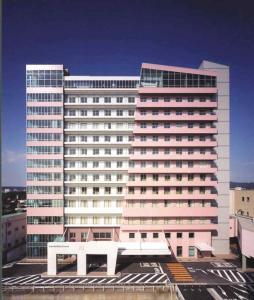

Worth the trek: Chiba's Kameda Hospital is staffed by physicians trained abroad.

Worth the trek: Chiba's Kameda Hospital is staffed by physicians trained abroad.

Harris recounts a personal story: "We had an experience at a large hospital, where we spent about an hour and a half with a specialist when the line behind us was very long and people kept coming to check to see if we were done yet. However, the doctor was happy to answer all of our questions." Harris recommends you do research until you have sufficient knowledge to ask intelligent questions and then put these to the physician. "Are they willing to answer, willing to discuss? That's what a patient should require of their provider if they are going to be putting themselves under their care. You have a right and obligation to question as much as you can. That is what we did, and we were very satisfied with the skill, the compassion, and the empathy of that provider."

Although finding the right individual physician is of great importance, Wocher believes that a good place to start is the hospital he manages. Last year, Kameda was ranked number 2 by the authoritatitive Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Inc. (See "Top 10 Japanese Hospitals," below). "We are voluntarily accredited," explains Wocher. "We have 350 years, 11 generations of committed physician leaders. We are passionate about this profession. We have the combination of a 'say yes' culture, and total commitment to the patient."

Kameda offers non-Japanese patients still other advantages. For one thing, it is managed by a Westerner in tune with their needs. What's more, many of its doctors are bilingual with overseas training, and they can provide medical record summaries in English.

Chiba's Kameda Hospital

Chiba's Kameda Hospital

Pressed to recommend hospitals outside his direct domain, Wocher is less forthcoming. "I am cautious about NOT recommending," Wocher says. "The dilemma is that, not every hospital is good at everything. It is always specific to the inquiry. However, for safe bets, I would say that those hospitals that have been ranked by Nikkei or Asahi - in the top 10 - have at least met the minimum requirement."

Wocher does let slip one other hospital name: "I do, however, have a great respect for St. Luke's - I know they have high patient satisfaction and have physicians trained abroad, like we do." Colby agrees with the general assessment of St. Luke's, where he had a positive experience: "One of our guests from Australia...passed out at dinner. We took him to St. Luke's, they did a MRI on his head within 20 minutes, at 11 pm. By 1 am we were leaving. We were thinking that we were gonna have a bill for like US$4,000 or something - but it was US$300 bucks!

Chiba's Kameda Hospital

Chiba's Kameda Hospital

Colby also appraises Kameda highly. He goes there for his biannual nigen-dokku. He also names The Tokyo Medical Clinic across from Tokyo Tower and Jikei University School of Medicine Hospital, which are both foreigner-friendly, and Sanno Hospital for neo-natal care. "But none of these places are cheap," he warns.

Expats might want to consider Johns Hopkins Medicine International, part of Tokyo Midtown, a complex rising at the former self-defense forces agency site in Roppongi and set to open in spring 2007. Johns Hopkins Medicine will oversee the entire management of the clinic, making it more like the Western clinics that expats are used to. The clinic is directly linked to its American counterpart in Baltimore, giving patients access to the Johns Hopkins Hospital, last year number one for the 15th consecutive year in US News & World Report's "America's Best Hospital Ranking."

Small Clinics versus Large Hospitals

For needs beyond a cold or the flu,Wocher expresses a word of caution when it comes to small clinics: "I am not a big fan of the 19-or-less-bed clinics because I think they fall outside of regulated accreditation...There is much less oversight of these 'mom and pop' clinics than there is for organizations like us."

Similarly, although Harris is reluctant to recommend any specific hospitals, he agrees with Wocher on the issue of small versus large institutions: "[At] larger hospitals, simply because they have a higher turnover and they are doing more procedures, one can expect to have greater access to more experienced staff. If the hospital is associated with a teaching institute, they probably have better access to more trained, more qualified staff."

Private vs Public Hospitals

This brings us to the subject of private versus public hospitals: Judging from the above opinions, you would assume that university hospitals, most of which are large and public, could provide better care. However, Wocher disagrees with this assessment: "Most of Japan's hospitals still remain fairly domestic. There is no competition with the National Health Insurance - and most of the large hospitals are public. There is more of a status quo here since it is so heavily regulated by the government." Private hospitals, on the other hand, are under less governmental bureaucracy. So they tend to be more committed to patient care than research and experimentation: "At Kameda, we have to...be more competitive because we do not rely on public funding. In this sense, I think private hospitals really have an incentive to try to improve."

Time to Go Home

For people with a medical problem who are due to be posted to Japan, Wocher advises having the local office research which facilities can provide the best care. "For example, if their kids have asthma, parents should figure out beforehand where to go if their child has an episode. Same with the expats who had surgery back in the home country and need follow-up care ringing a supply of medicine which is not available in Japan is a good idea. Expats should be prepared before they come."

In general, if language is a significant problem, and if you are uncomfortable with the lower level of information disclosure, then returning to your home country is a good idea if you have the time and the money. However, if language is not a problem, then the choice of staying in Japan versus going home for treatment really becomes condition-specific. Cancer care and psychiatry, for example, are deemed less sophisticated in Japan. Some paincontrol drugs for cancer patients are not available here, for instance. In fact, one of the major problems in the Japanese medical industry is the lack of physicians trained in radiology and oncology. In general, in cases that require long-term care and rehab, most people are more comfortable receiving care in their home country.

Conclusion

Choosing the right healthcare provider can be a daunting process anywhere, but the frustrations are often compounded when the patient is in a country where he or she has only a limited grasp of the language.

With the web now, we have a tool for people to educate themselves - perhaps not to the point where you know the answers, but at least to the point where you know the questions.

But despite structural differences between Western and Japanese healthcare, the basic message remains the same - people should be very proactive in seeking out what they want: "With the web now, we have a tool for people to educate themselves," Harris says, "perhaps not to the point where you know the answers, but at least to the point where you know the questions." Knowing the questions would then be the first step in finding the right physicians who can answer them.

We are happy to announce that John, our appendicitis patient/trooper, recovered from his successful surgery with little fanfare. He is a content father of two, married to a lovely Japanese woman and still living in Japan after nearly 15 years. He enjoys telling and re-telling his encounter with the Japanese hospital in between many bottles of wine during Thanksgiving dinners, held annually in his home. JI

*The choice of private and public would also not affect foreigners who make full use of their monthly NHI payments. All large hospitals take NHI; only small private clinics may not take NHI from foreigners.

| Top 10 Japanese Hospitals | ||||||

| Hospital | Prefecture | Patient friendliness | Safety | Quality of healthcare | Soundness of administration | Total score |

| Seirei Hamamatsu General | Shizuoka | 3 | 3 | 1 | 25 | 754 |

| Kameda Medical Center | Chiba | 6 | 71 | 2 | 19 | 707 |

| Seirei Mikatahara | Shizuoka | 11 | 1 | 21 | 49 | 706 |

| Kanto Medical Center NTT EC | Tokyo | 82 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 700 |

| Saisekai | Fukui | 7 | 38 | 17 | 22 | 687 |

| St. Luke's Intl. | Tokyo | 7 | 38 | 17 | 22 | 687 |

| Matsunami General | Gifu | 18 | 47 | 35 | 9 | 680 |

| Kariya General | Aichi | 18 | 13 | 13 | 49 | 671 |

| Asahi General | Chiba | 8 | 54 | 12 | 55 | 659 |

| Yokohama City Univ. | Kanagawa | 60 | 5 | 46 | 55 | 648 |

Source: Nikkei Shimbun survey of directors of important hospitals, 2005.

Beware Nosocomial Infections

Although many agree that Japanese hospitals are more than competent to handle primary care and non-life threatening illnesses, both Colby and Harris warn patients to be wary of infectious diseases. Interestingly enough, while the Japanese tend to be fastidious about cleanliness, with a long soak in the bath a daily ritual, the cult of cleanliness does not necessarily hold sway in hospitals and dental clinics. These often lack adequate systems for counteracting nosocomial infections, medical-speak for hospital born diseases. Mark Colby says routine hygiene is one area where the patient can make an empirical assessment of sufficiency: "You can watch - are people washing their hands. If it looks dirty and people are not doing, for example, standard hand washing, I would say you may want to look elsewhere." Guy Harris goes a step further: "Does the hospital give credence to the concept of 'wellness'? If the smell of tobacco permeates the air, for example, it probably doesn't [and] you might be better going elsewhere. -- E.K.