The OSE Is Not Dead Yet

Back to Contents of Issue: February 2003

|

|

|

|

by Alex Stewart |

|

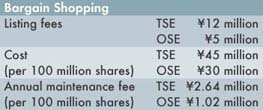

GORO TATSUMI IS DRIVEN. He founded a securities company while still in his 20s and has never looked back. As president of the Osaka Stock Exchange, he had ambitious plans to partner with Nasdaq and turn the second city's bourse into a global power. But that all fell apart last year with the announced departure of Nasdaq -- or did it? Tatsumi's final goal is to turn the OSE into a global force, and the smart money has not counted him out. The collapse of the Nasdaq Japan partnership between Nasdaq and the Osaka Stock Exchange last year seemed like bad news for the OSE. Since then, competition for new listings has intensified, and Nasdaq Japan's re-named successor, Hercules, does not look especially fitted to survive it. I met with the OSE's president, Goro Tatsumi, to find out what the OSE planned to do. Having met Tatsumi on other occasions, I did not expect to find him holding his head in his hands. He has the "vision thing," which helps him to look beyond setbacks. Talking with him, it became clear that the demise of Nasdaq Japan was not necessarily a setback, but an opportunity to pursue an even larger goal, one perhaps more suited to the operating framework and strengths of the OSE -- namely, to become a national exchange in the same way that Nasdaq Japan was planning to do. It had always been the goal of Nasdaq Japan to compete directly with the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE). To this end, it aimed to recruit the Japanese operations of large US companies like McDonald's, Microsoft and even IBM. It also wanted to list major stocks listed on the US Nasdaq so that Japanese investors could place orders through domestic brokers. The strength of the Nasdaq brand, however, meant that the OSE had limited say in how this would be achieved. When relations between the OSE and Nasdaq Japan became strained early in 2002, Nasdaq staff began to make approaches directly to Jasdaq, looking for a way to merge their operations. This would have been the worst scenario for the OSE. However, now that Nasdaq has left Japan (operations are due to be closed formally around March) the way is clear for the OSE to approach the Jasdaq instead. Tatsumi has the personality and leadership skills to push through a realignment of the securities trading market. A fan of American football and a martial arts expert, he looks and acts the part of a pugnacious salesman. Two things sustain his vision for the OSE. The first is to "globalize Kitahama," the area around the stock market. The alliance with Nasdaq is one part of this vision. The other is to offer competition to the TSE. Here, the experience of working with Nasdaq in the US was probably the key thing for Tatsumi. Tatsumi was elected president of the OSE in mid-2001, after the exchange ceased being a members' club and became a for-profit corporation. Before his election, he had been chairman of the Board of Governors. In recent years, the exchange had been run by retired bureaucrats from the Ministry of Finance, whose job was to represent the OSE's interests in the capital. This was useful when the nation's financial system was under the leadership of the ministry (the so-called "convoy" system), and everyone, including the OSE, had its place assigned. But times have changed. Tatsumi is from the financial industry, having founded one of the few genuinely independent brokerage houses in Japan, Kosei Securities, some 40 years ago when still only in his 20s. He has always been a shacho; there is no salaryman modesty, deference to the group or understatement in his manner or personality. This may explain why he has always managed very well in doing business with US exchanges and regulators, notably in futures and options trading. Tatsumi also has the kind of ambition that is pummeled out of most salarymen. It is what has driven him for 40 years, and as he explained to me at an earlier meeting before he became president of the exchange, the recovery of the OSE remains his final goal. Breaking from the convoy system The opportunity to break free of the convoy system came in December 1998, with the enactment of the Securities Trading Law, which made it possible to establish public trading systems. This opened the way for electronic communication networks in which brokers make markets in shares outside the established exchanges. It also opened the way for the entry of Nasdaq. In 1999, Nasdaq in the US had the money to make anything happen and had settled on a plan to create a global trading platform. It needed a partner in Asia, preferably Japan, to tie in the Asian time zone. Masayoshi Son, founder of Softbank, was the rainmaker who took up the challenge. Nasdaq could not easily set up in Japan without working through an existing exchange, because it needed to have a certain minimum number of securities companies as members. The only two candidates were the OSE or Jasdaq, since Nasdaq was planning to compete with the TSE just as it competes with the New York Stock Exchange in the US. The OSE, strongly encouraged by Tatsumi, accepted the challenge to host the new Nasdaq market, which opened in June 2000. It came into existence expecting to list 5,000 companies, including venture companies, large caps and stocks listed on other Nasdaq exchanges in the US and Europe. In terms of the number of listings, this would have made it twice as large as the TSE. The opportunity to tie up with Nasdaq did not come as a bolt out of the blue, however. Tatsumi told me in an earlier interview (J@pan Inc, August 2001) that he and directors of the US Nasdaq had been discussing ways to introduce the Nasdaq model to Japan for some years. Tatsumi's relationship with Nasdaq started in 1987, when Joseph Hardiman became president and CEO of the Nasdaq Exchange. Hardiman led the exchange until 1997, and Tatsumi says the two developed a close business and personal relationship during this period, mainly through meetings of the International Councils of Securities Dealers and Self-Regulatory Associations, which Tatsumi attended every year. Tatsumi subsequently also formed good relations with Frank Zarb, Hardiman's successor, and other senior management of Nasdaq International. "Whenever we met, we talked about our dreams of forming a tie-up between the OSE and Nasdaq and how we would do this," Tatsumi said in our earlier interview of those meetings with Hardiman and other Nasdaq officials. "Thus, whenever I was asked to draw up proposals for the reform of Japan's capital markets, I always proposed some form of partnership with the Nasdaq." He continued: "When we finally signed this agreement, I can tell you, it was like hitting a home run. What's more, I was so excited that I wanted to run past everyone on the team, hitting high fives just like you see on TV!" Tatsumi's enthusiasm for the alliance in 2001 belies the view I heard expressed in some parts of the Osaka securities community: Tatsumi never really had his heart in the alliance. Whatever his true feelings, he learned some important lessons during the brief alliance. For one, he learned that the OSE had the ability to create a second exchange in Japan for startups and large caps simultaneously, just like the Nasdaq had done in the US. He has always believed the OSE was a well-managed exchange, but after the experience of working with Nasdaq International, he learned that the OSE had the confidence and ability to do something more about it. In Tatsumi's words: Something -- anything -- could be a merger or alliance with Jasdaq to create real competition for the TSE. The OSE needs to team with a larger exchange that has better access to new initial public offering (IPO) listings. Jasdaq, on the other hand, lacks the know-how or experience to run a full listing exchange. The OSE appears to be run relatively well, and it is profitable, whereas the Jasdaq operates at a loss. Tatsumi says many of Jasdaq's members are becoming unhappy about this situation, and he adds ominously, "Many of the problems have not yet come to the surface, but they will become clearer." Although now an incorporated entity, Jasdaq remains, in the OSE's eyes, an unwieldy organization. In particular, it lacks leadership or vision, says Tatsumi. He can speak from first-hand knowledge, since he has worked closely with the Japan Securities Dealers Association as chairman of its Kansai committee for many years. One problem he points out is that its leading officers are changed every year or two, which means there is no long-term thinking. In contrast, says Tatsumi, "I am thinking deeply all the time about how to position the OSE and how to secure a long-term future for it."

Nippon New Market -- "Hercules"

The Jasdaq story Jasdaq is the market for smaller companies, originally called the OTC market. It was established in 1976, five years after Nasdaq in the US. The Nasdaq concept of providing a market designed specifically for smaller companies was evidently the chief model. The Japanese authorities decided that a special department supervised by the Japan Association of Securities Dealers should manage the exchange. It was not set up as a full exchange, like the TSE or OSE, but as a convenience for smaller companies. In February 2001, the department responsible for operating the exchange was incorporated. Currently, it has no plans to go public. By offering better listing terms for smaller companies, Jasdaq had attracted about 950 small businesses by the end of November. The establishment of the Nasdaq Japan market, followed by the TSE's incubator market, Mothers, created competition, but also stimulated the IPO market, so that the net effect on Jasdaq was positive. Despite its brand name and promise, Nasdaq Japan rarely accounted for more than one-quarter of the new listings in any month, and Mothers was much less successful still. What Tatsumi has in mind is to offer a Jasdaq Mark II, modeled on the success of Nasdaq -- i.e., a US model, not a home-grown one. Hercules by itself is not strong enough to emulate Nasdaq. A Jasdaq Mark II, however, could start with over 1,000 smaller cap stocks as well as the existing listings from the OSE. It would not be a venture exchange like Mothers, but a full exchange. Tatsumi's strategy is not to focus on the OSE but to create a brand new exchange, retaining the know-how of the OSE as a core element. He has no choice but to ally with Jasdaq to achieve this, since the majority of new issues derive from the Tokyo area. Because of this, he has already moved his main marketing operation to Tokyo. Although a true son of Osaka, Tatsumi's loyalty is to the exchange first. The OSE is planning to go public at the end of 2003, so time is of the essence. Regional pride Without doubt, there is an element of regional pride at stake as well. Osakans resent the way influence, not to mention profit, has moved to Tokyo. When Tatsumi entered the industry in the late 1950s, Osaka was still a major financial and commercial center. Before and after the war, 40 percent of share trading took place on the OSE. By the early 1980s, however, it had fallen to as low as 10 percent, putting the whole industry, including Tatsumi's company, Kosei Securities, into a deep crisis. It was arguably Tatsumi who helped put the OSE, and his own company, back on its feet. He was a key proponent of allowing the OSE to trade Nikkei futures and options. The Ministry of Finance agreed to the plan, and the OSE began trading futures in 1988, a year before the TSE. The Nikkei proved much more popular with traders, especially foreign brokerages, than the TSE's Topix. After all, it was Nikkei futures trading that brought down the house of Barings. The futures and options market is still dominated by foreign brokerage houses, hence the OSE's claim that it is an international exchange. The business is also the mainstay of the OSE's trading revenues: Fees earned on futures transactions account for as much as 80 percent of trading revenues. Without this business, the OSE might be only marginally more important than its country cousins in Nagoya or Fukuoka. The OSE has not allowed itself to become simply a feed for the Tokyo market, however. In fact, it has resisted that fate tooth and nail. And it had help from the bureaucrats, up until the Big Bang reforms of the 1990s kicked in; the Finance Ministry did everything it could to maintain the status quo between the players in the financial industry, including preserving a role for Osaka as a major exchange. While the OSE would be protected from going under, it also had to compete to earn its place in the financial "convoy." In return for this the ministry ensured that the TSE also had to try harder by, for example, introducing a derivatives trading market of its own.

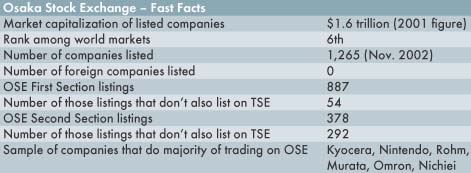

Waning influence But given the limited number of companies that depend on the OSE as a trading market (see "Fast Facts" box above), the bourse's value has become fairly marginal. The companies that have a single listing on the OSE tend to be smaller, family-owned businesses, with a domestic or regional business focus and a mainly regional shareholder base. They tend to have business models built around family succession rather than growth through the use of capital markets, so they are of limited interest to institutions or international funds. Thus, while they provide a source of listing income for the exchange, they provide very little fee income from trading. Another problem facing the OSE is that companies are no longer required to list shares on the nearest regional exchange. As a result, it is less attractive for many companies to have more than one listing, meaning that regional exchanges are losing customers. These are some of the obstacles facing the "tornado of Kitahama," as Tatsumi is known in Osaka securities circles. But he's been known to shake things up when he needs to. On becoming president of the OSE, the first thing he did was clear out the old guard, who had been allowed to establish 10 subsidiary companies, all loss making, without seeking approval of the board first. He closed down the companies and forced the resignation of most of those responsible. He called it "dealing with the accumulation of 125 years of old customs." He has pursued his reforms into the middle management layer, where he has encouraged the promotion of younger personnel if they show more aptitude. Tatsumi boasts that his exchange has better labor productivity than his Tokyo rival. He asserts that the OSE is quicker to adapt new technology -- a claim backed up by the fact that the OSE abolished floor trading first and was the first exchange outside the US to use the OptiMark system originally used by Nasdaq. Whatever claimed advantages the OSE has, the key to its ability to realign Japan's smaller exchanges into a global force lies in the fact that Tatsumi is a man with a mission in an industry where such people are few. One thought that he is obsessed with: Ensure that the TSE faces genuine competition. The shorthand to describe the monopoly he wants to break, which litters his conversation, is "only one." Politically, it may also be an argument that could win him support among members of the Japan Securities Dealers Association, who ultimately control the fate of Jasdaq. Tatsumi did not address at our meeting how the mechanics of creating a single exchange will work out. There are technical issues, issues of pride (would a new market be called "Hercules," for example?) and countless other obstacles to tackle before a new market can take shape. One fact working in the OSE's advantage is this: Tatsumi is a builder -- almost literally. Under his watch, the old OSE and its trading floor have been knocked down, and a new OSE is being built on top. He has built a new headquarters for his company, Kosei Securities, with a dramatic view of the river opposite Nomura's Osaka head office. There is also a new headquarters building in Tokyo, using the same London brick for facing (he said it conveys a message about globalization). Many problems in Japan remain unresolved due to the absence of decisive leadership. There is a broadly shared belief that Japan has too many exchanges; there is also support for giving the TSE more direct competition. It will require gusto and vision to achieve that goal. If Tatsumi can do it, the OSE will cease to be a regional exchange, and will become more like Nasdaq, a cross between an upstart exchange and an established one. That is also a metaphor for Tatsumi's own career: upstart broker in a status-driven industry and finally the head of an exchange that uses its experience to -- just maybe -- establish Japan's second truly international exchange. @ Alex Stewart is a contributing editor to J@pan Inc and our resident Kansai expert. His most recent article, How Gaijin is my Kansai?, appeared in our December issue. |

|

Note: The function "email this page" is currently not supported for this page.